or

Netherland-Brazil-Israel

Oct2013; photo courtesy from huffingtonpost

A Palestinian family's home in East Jerusalem was demolished in 2013 by the state municipality for not having proper safety permits. The family claimed they were still waiting for the permits to arrive.

........

Netherland's Limburg (Jesuits)

vs Amsterdam (Jews)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jewish_community_of_Amsterdam

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Limburg_(Netherlands)

For centuries, the strategic location of the current province made it a much-coveted region among Europe's major powers.Romans, Habsburg Spaniards, Prussians, Habsburg Austrians and French have all ruled Limburg.

The first inhabitants for whom traces have been found were Neanderthals that camped in South Limburg. In Neolithic timesflint was mined in underground mines; including one at Rijckholt that is available to visit. In Roman times Limburg was thoroughly Romanized and many existing towns and cities like Mosa Trajectum (Maastricht) and Coriovallum (Heerlen) were founded. Bishop Servatius introduced Christianity in Roman Maastricht, where he died in 384. After the Romans had departed the Franks took charge. The area flourished under Frankish rule. Charlemagne had his palace in nearbyAachen. After the partition of the Frankish empire the current Limburg belonged, like the rest of the Netherlands, to theHoly Roman Empire. The territory of Limburg was from the early Middle Ages usually divided between the Duchy of Brabant, Duchy of Gelderland, Duchy of Jülich, the Principality of Liège and the prince-bishop of Cologne. These dukes and bishops were nominal subordinates of the Emperor of the Roman Empire, but in practice they acted as independent sovereigns who were often at war amongst themselves. Their conflicts were often fought in the Limburg area, contributing to the fragmentation of the area.

The New time Limburg was largely divided between Spain (and its successor, Austria),Prussia, the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands, the Principality of Liège and many independent small Fiefs. In 1673, Louis XIV personally commanded the siege ofMaastricht by French troops. During the siege, one of his brigadiers, Charles de Batz-Castelmore d'Artagnan, perished. He subsequently became known as a major character in The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas, père (1802–1870).

Limburg was also the scene of many a bloody battle during the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648), in which the Dutch Republic threw off Habsburg Spanish rule. At the Battle of Mookerheyde (14 April 1574), two brothers of Prince William of Orange-Nassau and thousands of "Dutch" mercenaries lost their lives. Most Limburgians fought on the Spanish side, being Catholics and hating the Calvinist Hollanders.

Following the Napoleonic Era, the great powers (England, Prussia, the Austrian Empire, the Russian Empire and France) united the region with the new Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815. A new province was formed which was to receive the name "Maastricht" after its capital. The first king, William I, who did not want the name Limburg to be lost, insisted that the name be changed to "Province of Limburg". As such, the name of the new province derived from the old Duchy of Limburg that had existed until 1648 within the triangle of Maastricht, Liège, and Aachen.

When the Catholic and French-speaking Belgians split away from the mainly Calvinistnorthern Netherlands in the Belgian Revolution of 1830, the Province of Limburg was at first almost entirely under Belgian rule. However, by the 1839 Treaty of London, the province was divided in two, with the eastern part going to the Netherlands and the western part to Belgium, a division that remains today. With the Treaty of London, what is now the Belgian Province of Luxembourg was handed over to Belgium and removed from the German Confederation. To appease Prussia, which had also lost access to the Meuseafter the Congress of Vienna, the Dutch province of Limburg (but not the cities ofMaastricht and Venlo because without them the population of Limburg equalled the population of the Province of Luxembourg, 150,000 [1]), was joined to the German Confederation between September 5, 1839 and August 23, 1866 as Duchy of Limburg. On 11 May 1867, the Duchy, which from 1839 on had been de jure a separate polity in personal union with the Kingdom of the Netherlands, was re-incorporated into the latter with the Treaty of London. The style "Duchy of Limburg" however continued in some official use until February 1907. Another idiosyncrasy survives today: the head of the province, referred to as the "King's Commissioner" in other provinces, is addressed as "Governor" in Limburg.

The Second World War cost the lives of many civilians in Limburg, and a large number of towns and villages were destroyed by bombings and artillery battles. Various cemeteries, too, bear witness to this dark chapter in Limburg's history. Almost 8,500 Americansoldiers, who perished during the liberation of the Netherlands, lie buried at theNetherlands American Cemetery and Memorial in Margraten. Other big war cemeteries are to be found at Overloon (British soldiers) and the Ysselsteyn German war cemeterywas constructed in the Municipality of Venray for the 31,000 German soldiers who lost their lives.

In December 1991, the European Community (now European Union) held a summit in Maastricht. At that summit, the "Treaty on European Union" or so-called Maastricht treaty was signed by the European Community member states. With that treaty, the European Union came into existence.

Anthem[edit]

In 't Bronsgroen Eikenhout is the official anthem of both Belgian and Dutch Limburg.

Language[edit]

Main article: Limburgish language

Limburg has its own language, called Limburgish (Dutch: Limburgs). This has been an official regional language since 1997, and as such it receives moderate protection under Chapter 2 of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. It is not recognised by the Dutch, German and Belgian governments as an official language. Limburgish is spoken by an estimated 1.6 million people in both Belgian and Dutch Limburg and Germany.[citation needed] There are many different dialects in the Limburgish language. Almost every town and village has its own slightly different dialect. Dialects in the southeast (near Aachen) are closer to Ripuarian, and are sometimes classified as Southeast Limburgish. Even within the cities of Venlo and Maastricht, very different dialects separated by major isoglosses continue to exist.

Politics[edit]

The provincial council (Provinciale Staten) has 63 seats, and is headed by a King's Commissioner that is uniquely among Dutch provinces called the Governor. While the provincial council is elected by the inhabitants, the Governor is appointed by the King and the cabinet of the Netherlands. Since 2011 the Governor is Theo Bovens. The PVV is currently the largest party in the council.

The daily affairs of the province are taken care of by the Gedeputeerde Staten, which are also headed by the Governor; its members (gedeputeerden) can be compared with ministers.

Municipalities[edit]

Main article: Municipalities of Limburg (Netherlands)

Towns in Limburg[edit]

From North to South: Gennep, Venray, Weert, Venlo, Roermond, Sittard, Geleen, Heerlen, Valkenburg, Kerkrade, Vaals,Maastricht.

Geography[edit]

Unlike to the rest of the country the southern part of Limburg is quite hilly. The highest mountain in the continental part of the Netherlands, the Vaalserberg, is situated at Vaals, where at the so-called "Three-country-point" three countries (Netherlands, Belgium and Germany) are bordering.

Limburg's main river is the Meuse, that passes through the entire length of the province from South to North.

Limburg's surface is largely formed by deposits from this Meuse river, consisting of river clay, fertile loessial soil and large deposits of pebblestone, currently being quarried for the construction industry. In northern parts of the province, further away from the river bed, the soil primarily consists of sand and peat.

Limburg makes up one region of the International Organization for Standardization world region code system, having the code ISO 3166-2:NL-LI.

Economy[edit]

See also: Mining in Limburg

In the past peat and coal were mined in Limburg. In the period 1965–1975 the coal mines were finally closed. As a result in the two coal mining areas, Heerlen-Kerkrade-Brunssum and Sittard-Geleen, 60,000 people lost their jobs. A difficult period of economic re-adjustment started. The Dutch government partly eased the pain by moving several government offices (including Stichting Pensioenfonds ABP and CBS Statistics Netherlands) to Heerlen.

The state-owned corporation that once mined in Limburg, DSM, is now a major chemical company, still operating in Limburg.

Other industries include a car factory (in Born), Océ copiers and printers manufacturers in Venlo and a paper factory in Maastricht. There are four beer breweries.

Traditionally the southern part of Limburg has been one of the two main fruit growingareas of the country. Over the last some four decades however large fruit growing areas have been replaced by water, as a result of gravel quarrying near the river Meuse.

Tourism is an essential sector of the economy especially in the hilly southern part of the province. The town of Valkenburg is the main centre.

Since about 2005, when the two provincial newspapers "De Limburger" and "Limburgs Dagblad" merged, the one left is carrying both names.

Culture[edit]

Essential elements in Limburgian culture are

- Music (most places have their own brass-band);

- Religion (predominantly Roman Catholic);

- Folklore (in especially the southern part of the province);

- Carnival;

- Sports, of which especially bicycle racing and soccer are most popular;

- Art (among others architecture).

Music[edit]

As in many places there's a church chorus, choral singing is a notable kind of music in this province. One of the best known of these choruses is the "Mastreechter Staar" (Maastricht star), that also is performing nationally and internationally in purely secular contexts.

Fouryearly the World Music Contest, a competition for professional, amateur and military bands, (sometimes called 'the Olympic Games of brass band music') is held in Kerkrade. In 2013, like in 2009, the winner in the World Concert Division was the "Koninklijke Harmonie Sainte Cécile" from Eijsden (Limburg)[1]

Also in Kerkrade (situated on the German border) since 1973 in principle yearly the "Schlagerfestival" is held, a nationally broadcast event presenting performs of singers in the German-language popmusic category called "Schlagers".

Since 1969 yearly on the Pentecost weekend an international pop music festival calledPinkpop Festival takes place in the southern part of Limburg; initially at Geleen, since 1988 at Schaesberg.

More nationally or internationally known musicians from this province are mentioned hereunder in section "Famous Limburgians".

The Limburg Symphony Orchestra, that resided and rehearsed in Maastricht, and was the oldest symphony orchestra of the Netherlands (founded in 1883) following elimination of government grants merged with Het Brabants Orkest to form a single ensemble with the new name of the philharmonie zuidnederland, as of April 2013.[2]

Folklore[edit]

Many places in both Netherlands' and Belgian Limburg still have their own (by now folkloristic) citizen force. Yearly there's a festival, in which all 160 of them compete for the highest honours to be gained, in the "OLS" (Oud Limburgs Schuttersfeest), which is held in either a place in Belgian Limburg or in Netherlands' Limburg.

Sports[edit]

Soccer

In Limburg there are currently four professional soccer clubs, of which two, Roda JC Kerkrade and VVV-Venlo, compete in the Eredivisie, the highest national division. MVV Maastricht and Fortuna Sittard play in the Eerste Divisie, the second highest division.

Cycling

In 2012, for the sixth time, the UCI Road World Championships will be held in the hilly southern part of the province. The area also plays background to the Amstel Gold Raceclassic.

Handball

Team handball is the third most popular sport in Limburg. The women's team, HV Swift Roermond, has won the national championship in the highest division 19 times. The male teams, Sittardia (Sittard), Vlug en Lenig (Geleen) and BFC (Beek), which in 2008 merged as the Limburg Lions, have in total won the national championship 25 times.

Famous Limburgians[edit]

Politics, science, other

|

|

Entertainment, arts

|

|

Sports

|

|

(List of famous Belgian Limburgians: Famous Limburgians (Belgium))

Nature[edit]

In 2012 from April 5 till oktober 7 the ten yearly world horticulture expo "Floriade" was held in Venlo.

Nationally and internationally known are nature films and nature television series produced by filmdirector Maurice Nijsten and nature protector Jo Erkens.

Nature of Limburg (Gallery)[edit]

See also

Godfrey Henschen

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

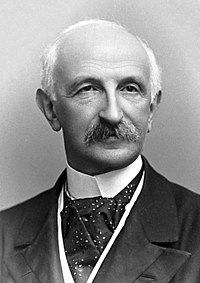

Godfrey Henschen, [1] (21 June 1601 – 11 September 1681) was a Belgian Jesuithagiographer, one of the first Bollandists.[2]

Henschen was born at Venray, Limburg, in the Low countries. He was the son of Henry Henschen, a cloth merchant, and Sibylla Pauwels. He studied the humanities at the Jesuit college of Bois-le-Duc (today the town of 's-Hertogenbosch) and entered the novitiate of the Society of Jesus at Mechlin on 22 October 1619. He taught successively Greek, poetry and rhetoric at Bergues, Bailleul, Ypres, andGhent. He was ordained a priest on 16 April 1634, sent to the professed house atAntwerp the following year, and admitted to the profession of the four Jesuit vows on 12 May 1636.

From the time of his arrival in the city he was associated as collaborator with his fellow Jesuit, Jean Bolland, who was then preparing the first volumes of the Acta Sanctorum. It was Henschen who, by his commentary on the Acts of St. Amand, suggested to Bolland the course to follow, and gave to the work undertaken by his mentor its definitive form.

At Bolland's direction, Henschen journeyed in company with Daniel van Papenbroek, to Italy, France, and Germany (22 July 1660-21 December 1662) to collect ancient documents for their studies. Upon their return, they learned that Bolland had died, at which point he and Papenbroek began to lead the project. He was the first librarian of the Museum Bollandianum at Antwerp.

Henschen died at Antwerp, aged 80, in 1681.

Works[edit]

Henschen collaborated on the volumes for January, February, March, and April, and on the first six volumes for May, that is on seventeen volumes of the Acta Sanctorum. Several of his posthumous commentaries appeared in the succeeding volumes. A list of some other works from his pen will be found in Augustin de Backer's Bibliothèque des escrivains de la Compagnie de Jésus.

========================================Amsterdam Jews

ewish community of Amsterdam

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Amsterdam has historically been the center of the Dutch Jewish community, and has had a continuing Jewish community for the last 370 years.[1] Amsterdam is also known under the name "Mokum", given to the city by its Jewish inhabitants ("Mokum" is Yiddish for "town", derived from the Hebrew "makom", which literally means "place"). Although the Holocaust deeply affected the Jewish community, killing some 80% of the some 80,000 Jews at time present in Amsterdam, since then the community has managed to rebuild a vibrant and living Jewish life for its approximately 15,000 present members. The former Mayor of Amsterdam, Job Cohen, is Jewish. Cohen was runner-up for the award of World Mayor in 2006.[2][3]

Marranos and Sephardic Jews[edit]

Permanent Jewish life in Amsterdam began with the arrival of pockets ofMarranos and Sephardic Jews at the end of the 15th, and beginning of the 16th century. Although many Sephardim (so-called Spanish Jews) had been expelled from Spain and Portugal in 1492 after the fall of muslim Granada.

From 1497, others remained in the Iberian peninsula, practising Judaism in secret. The newly independent Dutch provinces provided an ideal opportunity for these crypto-Jews to re-establish themselves and practise their religion openly, and they migrated, most notably to Amsterdam. Collectively, they brought trading influence to the city as they established in Amsterdam.

In 1593 these Marranos arrived in Amsterdam after having been refused admission to Middelburg and Haarlem. These Jews were important merchants and persons of great ability. Their expertise, it can be stated, contributed materially to the prosperity of the country. They became strenuous supporters of the House of Orange and were in return protected by the stadholder. At this time the commerce of Holland was increasing; a period of development had arrived, particularly for Amsterdam, to which Jews had carried their goods and from which they maintained their relations with foreign lands. Quite new for the Netherlands, they also held connections with the Levant and Morocco.

The formal independence from Spain of the Republic of the Seven United Provinces (1581), theoretically opened the door to public practice of Judaism. Yet only in 1603 did a gathering take place that was licensed by the city. Three congregations formed in the 1610s which merged to form a united Sephardic congregation in 1639.

Ashkenazim[edit]

The first Ashkenazim who arrived in Amsterdam were refugees from the Chmielnicki Uprising in Poland and the Thirty Years War. Their numbers soon swelled, eventually outnumbering the Sephardic Jews at the end of the 17th century; by 1674, some 5,000 Ashkenazi Jews were living in Amsterdam, while 2,500 Sephardic Jews called Amsterdam their home.[4]Many of the new Ashkenazi immigrants were poor, contrary to their relatively wealthy Sephardic co-religionists. They were only allowed in Amsterdam because of the financial aid promised to them and other guarantees given to the Amsterdam city council by the Sephardic community, despite the religious and cultural differences between the Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazim and the Portuguese-speaking Sephardim.

Only in 1671 did the large Ashkenazi community inaugurate their own synagogue, the Great Synagogue,[5] which stood opposite to the Sephardic Esnoga Synagogue.[6] Soon after, several other synagogues were built, among them the Obbene Shul[7] (1685-1686), the Dritt Shul[8] (1700) and the Neie Shul[9] (1752, also known as the New Synagogue). For a long time, the Ashkenazi community was strongly focused on Central and Eastern Europe, the region where most of the Dutch Ashkenazi originated from. Rabbis, cantors and teachers hailed from Poland and Germany. Up until the 19th century, most of the Ashkenazi Jews spoke Yiddish, with some Dutch influences. Meanwhile, the community grew and flourished. At the end of the 18th century, the 20,000-strong Ashkenazi community was one of the largest in Western and Central Europe.[4]

The Holocaust[edit]

The Germans occupied the Netherlands on May 10, 1940, and established a civilian administration dominated by the SS. Amsterdam, the country's largest city, had a Jewish population of about 75,000 (including, notably, Anne Frank), which increased to over 79,000 in 1941. Jews represented less than 10 percent of the city's total population. More than 10,000 of these were foreign Jews who had found refuge in Amsterdam in the 1930s.

On February 22, 1941, the Germans arrested several hundred Jews and deported them from Amsterdam first to the Buchenwald concentration campand then to the Mauthausen concentration camp. Almost all of them were murdered in Mauthausen. The arrests and the brutal treatment shocked the population of Amsterdam. In response, Communist activists organized a general strike on February 25, and were joined by many other worker organizations. Major factories, the transportation system, and most public services came to a standstill. The Germans brutally suppressed the strike after three days, crippling Dutch resistance organizations in the process.

In January 1942, the Germans began the relocation of provincial Jews to Amsterdam. Within Amsterdam, Jews were restricted to certain sections of the city. Foreign and stateless Jews were sent directly to the Westerbork transit camp. In July 1942, the Germans began mass deportations of Jews to extermination camps in occupied Poland, primarily to Auschwitz but also toSobibor. The city administration, the Dutch municipal police, and Dutch railway workers all cooperated in the deportations, as did the Dutch Nazi party (NSB). German and Dutch Nazi authorities arrested Jews in the streets of Amsterdam and took them to the assembly point for deportations - the municipal theater building, the Hollandsche Schouwburg[10] When several hundred people were assembled in the building and in the back courtyard, they were transferred to Westerbork. In October 1942, the Germans sent all Jews in forced-labor camps and their families to Westerbork. All were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau within a few weeks.

In May 1943, German authorities ordered 7,000 Jews, including employees of the Judenrat in Amsterdam, to assemble in an Amsterdam city square for deportation. Only 500 people complied. The Germans responded by sealing the Jewish quarter and rounding up Jews. From May through September 1943, the Germans launched raids to seize Jews in the city.[11]

The Germans confiscated the property left behind by deported Jews. In 1942 alone the contents of nearly 10,000 apartments in Amsterdam were expropriated by the Germans and shipped to Germany. Some 25,000 Jews, including at least 4,500 children, went into hiding to evade deportation. About one-third of those in hiding were discovered, arrested, and deported. In all, at least 80 percent of the prewar Dutch Jewish community perished.

In the spring of 1945, the Canadian Forces liberated Amsterdam.

Cheider[edit]

In 1964 Adje Cohen began Jewish classes with five children in his home. This grew into an Orthodox Jewish school (Yeshiva) that provides education for children from kindergarten through high school. Many Orthodox families would have left The Netherlands if not for the existence of the Cheider[citation needed]: Boys and girls learn separately as orthodox Judaism requires, and the education is with a greater focus on the religious needs. By 1993 the Cheider had grown to over 230 pupils and 60 Staff members. The Cheider moved into its current building at Zeeland Street in Amsterdam Buitenveldert. Many prominent Dutch Figures attended the opening, most noteworthy was Princess Margriet who opened the new building.[12][13]

Jewish community in the 21st Century[edit]

Most of the Amsterdam Jewish community (excluding the Progressive and Sephardic communities) is affiliated to theAshkenazi Nederlands Israëlitisch Kerkgenootschap. These congregations combined form the Nederlands-Israëlietische Hoofdsynagoge (NIHS) (the Dutch acronym for the Jewish Community of Amsterdam). Some 3,000 Jews are formally part of the NIHS.[1] The Progressive movement currently has some 1,700 Jewish members in Amsterdam, affiliated to the Nederlands Verbond voor Progressief Jodendom. Smaller Jewish communities include the SephardicPortugees-Israëlitisch Kerkgenootschap (270 families in and out of Amsterdam) and Beit Ha'Chidush, a community of some 200 members and 'friends' connected to Jewish Renewal and Reconstructionist Judaism. Several independent synagogues exist as well.[14] The glossy Joods Jaarboek (Jewish Yearbook), is based in Amsterdam, as well as the weekly Dutch Jewish newspaper in print: the Nieuw Israëlitisch Weekblad.

Contemporary Synagogues[edit]

There are functioning synagogues in Amsterdam at the following addresses.

Ashkenazi: Nederlands Israëlitisch Kerkgenootschap (Modern Orthodox; Orthodox)

- Gerard Doustraat 238 (the Gerard Dou Synagogue)[15] (congregation Tesjoengat Israël)[16]

- Gerrit van der Veenstraat 26 (the Kehillas Ja'akov)[17]

- Jacob Obrechtplein/Heinzestraat 3 (the synagogue is called the Raw Aron Schuster Synagogue)[18]

- Lekstraat 61 (the Lekstraat Synagogue built in 1937; Charedi)[19]

- Nieuwe Kerkstraat 149 (called the Russische sjoel or Russian Shul)[20]

- Vasco de Gamastraat 19 (called the Synagogue West due to its location in the west of Amsterdam)

- There is also a synagogue present in Jewish nursing home Beth Shalom[21]

Progressive: Nederlands Verbond voor Progressief Jodendom(Progressive)

- Jacob Soetendorpstraat 8[22]

Reconstructionist: Beit Ha'Chidush (Jewish Renewal/Reconstructionist Judaism/Liberal Judaism)

- Nieuwe Uilenburgerstraat 91 (called the Uilenburg Synagogue)[23]

Sephardic: Portugees-Israëlitisch Kerkgenootschap (Sephardic Judaism)

- Mr. Visserplein 3 (the Esnoga Synagogue)

Kashrut in Amsterdam[edit]

Kosher food in Amsterdam restaurants and shops is available.[24] There is the possibility of eating kosher in Restaurant Ha-Carmel,[25] and the well-known Sandwichshop Sal-Meijer.[26]

Jewish Culture[edit]

The Joods Historisch Museum[27] is the center of Jewish culture in Amsterdam. Other Jewish cultural events include the Internationaal Joods Muziekfestival (International Jewish Music Festival)[28] and the Joods Film Festival (Jewish Film Festival).[29]

The Anne Frank House hosts a permanent exhibit on the story of Anne Frank.

Jewish Cemeteries[edit]

Six Jewish cemeteries exist in Amsterdam and surroundings, three OrthodoxAshkenazi (affiliated to the NIK), two linked to the Progressive community and one Sephardic. The Askhenazi cemetery[30] at Muiderberg is still frequently used by the Orthodox Jewish community. The Orthodox Ashkenazi cemetery[31]at Zeeburg, founded in 1714, was the burial ground for some 100,000 Jews between 1714 and 1942. After part of the ground of the cemetery was sold in 1956, many graves were transported to theOrthodox Ashkenazi Jewish cemetery[32] near Diemen (also still in use, but less frequent than the one in Muiderberg). A Sephardic cemetery, Beth Haim,[33] exists near the small town of Ouderkerk aan de Amstel, containing the graves of some 28,000 Sephardic Jews. Two Progressive cemeteries, one[34] in Hoofddorp (founded in 1937) and one[34] in Amstelveen (founded in 2002), are used by the large Progressive community.

History of the Jews in the Netherlands

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

|

|

|

Most history of the Jews in the Netherlands was generated between the end of the 16th century and World War II.

The area now known as the Netherlands was once part of the Spanish Empire but in 1581, the northern Dutch provinces declared independence. A principal motive was a wish to practice Protestant Christianity, then forbidden under Spanish rule, and so religious tolerance was effectively an important constitutional element of the newly independent state. This inevitably attracted the attention of Jews who were religiously oppressed in many parts of the world.

Contents

[hide]History of Jews in the Netherlands[edit]

Early history[edit]

Jews seem to have lived in the province of Holland before 1593; a few references to them are in existence which distinctly mention them as present in the other provinces at an earlier date, especially after their expulsion from France in 1321 and the persecutions in Hainaut and the Rhine provinces. The first Jews in the province of Gelderland were reported in 1325. Jews have been settled inNijmegen, the oldest settlement, in Doesburg, Zutphen, and in Arnhem since 1404. In 1349 the Duke of Guelders was authorized by the Emperor Louis IV of the Holy Roman Empire of Germany to receive Jews in his duchy. They paid a tax, granted services, and were protected by the law. In Arnhem, where a Jew is mentioned as a physician, the magistrate defended them against the hostilities of the populace. When Jews settled in the diocese of Utrecht does not appear. (However, rabbinical records regarding kashrut – Jewish dietary laws – speculated that the Jewish community in Utrecht dated back to Roman times.) In 1444 they were expelled from the city of Utrecht, but they were tolerated in the village ofMaarssen, two hours distant, though their condition was not fortunate. Until 1789 no Jew might pass the night in Utrecht; for this reason the community of Maarssen was one of the most important in the Netherlands. Jews were admitted to Zeeland by Albert, Duke of Bavaria.

In 1477, by the marriage of Mary of Burgundy to the Archduke Maximilian, son of Emperor Frederick III, the Netherlands were united to Austria and its possessions passed to the crown of Spain. In the sixteenth century, owing to the persecutions of Charles V and Philip II of Spain, the Netherlands became involved in a series of desperate and heroic struggles. Charles V had, in 1522, issued a proclamation against Christians who were suspected of being lax in the faith and against Jews who had not been baptized in Gelderland and Utrecht; and he repeated these edicts in 1545 and 1549. In 1571 the Duke of Alba notified the authorities of Arnhem that all Jews living there should be seized and held until the disposition to be made of them had been determined upon. In 1581, however, the memorable declaration of independence (Act of Abjuration) issued by the deputies of the United Provinces deposed Philip from his sovereignty; religious peace was guaranteed by article 13 of the Unie van Utrecht. As a consequence the persecuted Jews of Spain and Portugal turned toward Holland as a place of refuge.

Marranos and Sephardic Jews[edit]

The Sephardim (so-called Spanish Jews) had been expelled from Spain and Portugal years earlier, but many remained in the Iberian peninsula, practising Judaism in secret (see crypto-Jews or Marranos). The newly independent Dutch provinces provided an ideal opportunity for the crypto-Jews to re-establish themselves and practise their religion openly, and they migrated, most notably to Amsterdam. Collectively, they brought trading influence to the city as they established in Amsterdam.

In 1593 these Marranos arrived in Amsterdam after having been refused admission to Middelburg and Haarlem. These Jews were important merchants and persons with in-demand skills. They labored assiduously in the cause of the people and contributed materially to the prosperity of the country. They became strenuous supporters of the House of Orangeand were in return protected by the stadholder. At this time the commerce of Holland was increasing; a period of development had arrived, particularly for Amsterdam, to which Jews had carried their goods and from which they maintained their relations with foreign lands. Thus they had connections with the Levant and with Morocco. The Emperor of Morocco had an ambassador at The Hague named Samuel Pallache (1591–1626), through whose mediation, in 1620, a commercial understanding was arrived at with the Barbary States.

In particular, the relations between the Dutch and South America were established by Jews; they contributed to the establishment of the Dutch West Indies Company in 1621, of the directorate of which some of them were members. The ambitious schemes of the Dutch for the conquest of Brazil were carried into effect through Francisco Ribiero, a Portuguese captain, who is said to have had Jewish relations in Holland. As some years afterward the Dutch in Brazil appealed to Holland for craftsmen of all kinds, many Jews went to Brazil; about 600 Jews left Amsterdam in 1642, accompanied by two distinguished scholars – Isaac Aboab da Fonseca and Moses Raphael de Aguilar. In the struggle between Holland and Portugal for the possession of Brazil the Dutch were supported by the Jews.

With various countries in Europe also the Jews of Amsterdam established commercial relations. In a letter dated 25 November 1622, King Christian IV of Denmark invites Jews of Amsterdam to settle in Glückstadt, where, among other privileges, the free exercise of their religion would be assured to them.

Besides merchants, a great number of physicians were among the Spanish Jews in Amsterdam: Samuel Abravanel, David Nieto, Elijah Montalto, and the Bueno family; Joseph Bueno was consulted in the illness of Prince Maurice (April, 1623). Jews were admitted as students at the university, where they studied medicine as the only branch of science which was of practical use to them, for they were not permitted to practise law, and the oath they would be compelled to take excluded them from the professorships. Neither were Jews taken into the trade-guilds: a resolution passed by the city of Amsterdam in 1632 (the cities being autonomous) excluded them. Exceptions, however, were made in the case of trades which stood in peculiar relations to their religion: printing, bookselling, the selling of meat, poultry, groceries, and drugs. In 1655 a Jew was, exceptionally, permitted to establish a sugar-refinery. One particular Sephardic Jew also stood out during that time: his name was Benedictus de Spinoza (or Baruch Spinoza). He was excommunicated from the Jewish community in 1656 after speaking out his ideas concerning (the nature of) God later published in his famous work Ethics.

Ashkenazim[edit]

Many Ashkenazim (so-called "German Jews") were also attracted to the newly independent Dutch provinces, especially near the end of the 17th century. However, most were displaced migrants escaping persecution in other parts of northern Europe, in particular the violence of the Thirty Year War (1618–1648) and the Chmielnicki Uprising in Poland in 1648. Because most of the immigrants were poor, they were less welcome. Their arrival in considerable number threatened the economic status of Amsterdam in particular, and with few exceptions they were turned away. Generally, they settled in rural areas where they subsisted typically as pedlars and hawkers. The result was that a large number of small Jewish communities existed throughout the Dutch provinces.

Over time, many of these German Jews attained prosperity through retail trading and by diamond-cutting, in which latter industry they retained the monopoly until about 1870. When William IV was proclaimed stadholder (1747) the Jews found another protector like William III. He stood in very close relations with the head of the DePinto family, at whose villa, Tulpenburg, near Ouderkerk, he and his wife paid more than one visit. In 1748, when a French army was at the frontier and the treasury was empty, De Pinto collected a large sum and presented it to the state. Van Hogendorp, the secretary of state, wrote to him: "You have saved the state." In 1750 De Pinto arranged for the conversion of the national debt from a 4 to a 3% basis.

Under the government of William V the country was troubled by internal dissensions; the Jews, however, remained loyal to him. As he entered the legislature on the day of his majority, 8 March 1766, everywhere in the synagogues services of thanks-giving were held. William V did not forget his Jewish subjects. On 3 June 1768, he visited both the German and the Portuguese synagogue; he attended the marriage of various prominent Jewish families.

The French Revolution and Napoleon[edit]

The year 1795 brought the results of the French Revolution to Holland, including emancipation for the Jews. The National Convention, on 2 September 1796, proclaimed this resolution: "No Jew shall be excluded from rights or advantages which are associated with citizenship in the Batavian Republic, and which he may desire to enjoy." Moses Moresco was appointed member of the municipality at Amsterdam; Moses Asser member of the court of justice there. The old conservatives, at whose head stood the chief rabbi Jacob Moses Löwenstamm, were not desirous of emancipation rights. Indeed, these rights were for the greater part of doubtful advantage; their culture was not so far advanced that they could frequent ordinary society; besides, this emancipation was offered to them by a party which had expelled their beloved Prince of Orange, to whose house they remained so faithful that the chief rabbi at The Hague, Saruco, was called the "Orange dominie"; the men of the old régime were even called "Orange cattle." Nevertheless, the Revolution appreciably ameliorated the condition of the Jews; in 1799 their congregations received, like the Christian congregations, grants from the treasury. In 1798 Jonas Daniel Meijer interceded with the French minister of foreign affairs in behalf of the Jews of Germany; and on 22 Aug. 1802, the Dutch ambassador, Schimmelpenninck, delivered a note on the same subject to the French minister.

From 1806 to 1810 Holland was ruled by Louis Bonaparte, whose intention it was to so amend the condition of the Jews that their newly acquired rights would become of real value to them; the shortness of his reign, however, prevented him from carrying out his plans. For example, after having changed the market-day in some cities (Utrecht and Rotterdam) from Saturday to Monday, he abolished the use of the "Oath More Judaico" in the courts of justice, and administered the same formula to both Christians and Jews. To accustom the latter to military services he formed two battalions of 803 men and 60 officers, all Jews, who had been until then excluded from military service, even from the town guard.

The union of Ashkenazim and Sephardim intended by Louis Napoleon did not come about. He had desired to establish schools for Jewish children, who were excluded from the public schools; even the Maatschappij tot Nut van 't Algemeen, founded in 1784, did not willingly receive them or admit Jews as members. Among the distinguished Jews of this period were Meier Littwald Lehemon, Mozes Salomon Asser, Capadose, and the physicians David Heilbron, Davids (who introduced vaccination), Stein van Laun (tellurium), and many others.[1]

19th century and early 20th century[edit]

On 30 November 1813, William VI arrived at Scheveningen, and on 11 December he was solemnly crowned as King William I.

Chief Rabbi Lehmans of The Hague organized a special thanksgiving service and implored God's protection for the allied armies on 5 January 1814. Many Jews fought at Waterloo, where thirty-five Jewish officers died. William VI concerned himself with the organisation of the Jewish congregations. On 26 February 1814, a law was promulgated abolishing the French régime. The Jews continued to prosper in the independent Holland throughout the 19th century. By 1900, Amsterdam had 51,000 Jews with 12,500 paupers, The Hague 5,754 Jews with 846, Rotterdam 10,000 with 1,750, Groningen 2,400 with 613, Arnhem 1,224 with 349 ("Joodsche Courant," 1903, No. 44). The total population of the Netherlands in 1900 was 5,104,137, about 2% of whom were Jews.

The Netherlands, and Amsterdam in particular, remained a major Jewish population centre until World War II, so much so that Amsterdam was calledJerusalem of the West by its Jews. The latter part of the 19th century, as well as the first decades of the 20th century, saw an ever-expanding Jewish community in Amsterdam after Jews from themediene (the "country" Jews, Jews who were living outside the big cities – like Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague -, in numerous small congregations throughout the Dutch countryside) left their communities en masse, searching for a "better life" in the larger cities.

Dutch Jews were a relatively small part of the population and showed a strong tendency towards internal migration, which led to them being integrated into the socialist and liberal "pillars" before the Holocaust, rather than becoming part of a Jewish pillar.[2]

The number of Jews in the Netherlands grew substantially from the early 19th century up to World War II. Between 1830 and 1930, the Jewish presence in the Netherlands increased by almost 250% (numbers given by the Jewish communities to the Dutch Census).

| Year | Number of Jews | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1830 | 46,397 | Census* |

| 1840 | 52,245 | Census* |

| 1849 | 58,626 | Census* |

| 1859 | 63,790 | Census* |

| 1869 | 67,003 | Census* |

| 1879 | 81,693 | Census* |

| 1889 | 97,324 | Census* |

| 1899 | 103,988 | Census* |

| 1909 | 106,409 | Census* |

| 1920 | 115,223 | Census* |

| 1930 | 111,917 | Census* |

| 1941 | 154,887 | Nazi occupation** |

| 1947 | 14,346 | Census* |

| 1954 | 23,723 | Commission on Jewish Demography*** |

| 1960 | 14,503 | Census* |

| 1966 | 29,675 | Commission on Jewish Demography*** |

(*) Derived from those persons who stated "Judaism" as their religion in the Dutch Census

(**) Persons with at least one Jewish grandparent. In another Nazi census the total number of people with at least one Jewish grandparent in the Netherlands was put at 160,886: 135,984 people with 4 or 3 Jewish grandparents (counted as "full Jews"); 18,912 Jews with 2 Jewish grandparents ("half Jews"), of whom 3,538 were part of a Jewish congregation; 5,990 with 1 Jewish grandparent ("quarter Jews")[4]

(***) Membership numbers of Dutch Jewish congregations (only those who are Jewish according to the Halakha)

The Holocaust[edit]

Main article: The Holocaust

In 1939, there were some 140,000 Dutch Jews living in the Netherlands, among them some 25,000 German-Jewish refugees who had fled Germany in the 1930s (other sources claim that some 34,000 Jewish refugees entered the Netherlands between 1933 and 1940, mostly from Germany and Austria).[5] The Nazi occupation force put the number of (racially) Dutch Jews in 1941 at some 154,000. In the Nazi census, some 121,000 persons declared they were members of the (Ashkenazi) Dutch-Israelite community; 4,300 persons declared they were members of the (Sephardic) Portuguese-Israelite community. Some 19,000 persons reported having two Jewish grandparents (although it is generally believed a proportion of this number had in fact three Jewish grandparents, but declined to state that number for fear that they would be seen as Jews instead of half-Jews by the Nazi authorities). Some 6,000 persons reported having one Jewish grandparent. Some 2,500 persons who were counted in the census as Jewish were members of a Christian church, mostly Dutch Reformed,Calvinist Reformed or Roman Catholic.

In 1941, most Dutch Jews were living in Amsterdam. The census in 1941 gives an indication of the geographical spread of Dutch Jews at the beginning of World War II (province; number of Jews – this number is not based on the racial standards of the Nazis, but by what the persons declared themselves to be in the population census):

- Groningen – 4,682

- Friesland – 851

- Drenthe – 2,498

- Overijssel – 4,345

- Gelderland – 6,663

- Utrecht – 4,147

- North Holland – 87,026 (including 79,410 in Amsterdam)

- South Holland – 25,617

- Zeeland – 174

- North Brabant – 2,320

- Limburg – 1,394

- Total – 139,717

In 1945, only about 35,000 of them were still alive. The exact number of "full Jews" who survived the Holocaust is estimated to be 34,379 (of whom 8,500 were part of a mixed marriage and thus spared deportation and possible death in the Nazi concentration camps); the number of "half Jews" who were present in the Netherlands at the end of the Second World War in 1945 is estimated to be 14,545, the number of "quarter Jews" 5,990.[4] Some 75% of the Dutch-Jewish population perished, an unusually high percentage compared with other occupied countries in western Europe.[6]

Factors that influenced the great number of people who perished were the fact that the Netherlands was not under a military regime, because the queen and the government had fled to England, leaving the whole governmental apparatus intact. An important factor is also that Holland at that time was already the most densely inhabited country of Western Europe, making it difficult for the relatively large number of Jews to go into hiding, if they would have chosen to. Most Jews in Amsterdam were poor, which limited their options for flight or hiding. Another factor is that the country did not have much open space or woods to flee to. Also, the civil administration was advanced and offered the Nazi-German a full insight in not only the numbers of Jews, but also where they exactly lived.

A theory is that the vast majority of the nation accommodated itself to circumstances: "In their preparations for the extermination of the Jews living in The Netherlands, the Germans could count on the assistance of the greater part of the Dutch administrative infrastructure. The occupiers had to employ only a relatively limited number of their own. Dutch policemen rounded up the families to be sent to their deaths in Eastern Europe. Trains of the Dutch railways staffed by Dutch employees transported the Jews to camps in The Netherlands which were transit points to Auschwitz, Sobibor, and other death camps." With respect to Dutch collaboration, Eichmann quoted as saying 'The transports run so smoothly that it is a pleasure to see.'[7]

During the first year of the occupation of the Netherlands, Jews, who were already, just as Protestants or Catholics, registered on basis of their faith with the authorities had to get a large 'J' stamped in their IDs while the whole population had to declare wether or not they had 'Jewish' roots. Jews were banned from certain occupations and further isolated from public life. Starting in January 1942, some Dutch Jews were forced to move to Amsterdam; others were directly deported to Westerbork, a concentration camp near the small village of Hooghalen which had been founded in 1939 by the Dutch government to give shelter to Jews fleeing Nazi persecution, but would fulfill the function of a transit camp to the Nazi death camps in Middle and Eastern Europe during World War II.

All non-Dutch Jews were also sent to Westerbork. In addition, over 15,000 Jews were sent to labour camps. Deportations of Jews from the Netherlands to Poland and Germany began on 15 June 1942 and ended on 13 September 1944. Ultimately some 101,000 Jews were deported in 98 transports from Westerbork to Auschwitz (57,800; 65 transports), Sobibor (34,313; 19 transports), Bergen-Belsen (3,724; 8 transports) and Theresienstadt (4,466; 6 transports), where most of them were murdered. Another 6,000 Jews were deported from other locations (like Vught) in the Netherlands to concentration camps in Germany, Poland and Austria (like Mauthausen). Only 5,200 survived. The Dutch underground hid an estimated number of Jews of some 25,000–30,000; eventually, an estimated 16,500 Jews managed to survive the war by hiding. Some 7,000 to 8,000 survived by fleeing to countries like Spain, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland, or by being married to non-Jews (which saved them from deportation and possible death). At the same time, there was substantial collaboration from the Dutch population including the Amsterdam city administration, the Dutch municipal police, and Dutch railway workers who all helped to round up and deport Jews.

One of the best known Holocaust victims in the Netherlands is Anne Frank. Along with her sister, Margot Frank, she died from typhus in March 1945 in the concentration camp of Bergen-Belsen, due to unsanitary living conditions and confinement by the Nazis. Anne Frank's mother, Edith Frank-Holländer, was starved to death by the Nazis in Auschwitz. Anne Frank's father, Otto Frank, survived the war. Dutch victims of the Holocaust include Etty Hillesum,[8] Abraham Icek Tuschinski and Edith Stein a.k.a. Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross.

In contrast to many other countries where all aspects of Jewish communities and culture were eradicated during the Shoah, a remarkably large proportion of rabbinic records survived in Amsterdam, making the history of Dutch Jewry unusually well documented.

Yad Vashem[edit]

The Dutch received the relatively largest number of awards from Yad Vashem for saving Jews: in total (2013) the number is over 5,200 and counting - Poles were awarded over 6,100 awards, but the Dutch received 1 for every 1,800 Dutch, against 1 in every 4,300 in the case of the Poles.[9] Remarkable is also that only the Dutch received three Yad Vashem awards for groups or organisations:

- for the collective of the about 40-50,000 stikers of the February Strike of 25–26 February 1941 against deportation of Jews from Holland

- for the village of Nieuwlande in the province of Drenthe, where the whole population took part in hiding Jews

- for the so-called 'NV' ("Naamloze vennootschap", anonymous partnership or limited company); this organisation from Utrecht specialised in saving and hiding Jewish children, some 600, all of whom survived the war.

Also the exploits of Truus Wijsmuller-Meijer in saving especially children outside Holland from the shoah, are noted. She organised the first train tranport of 600 Jewish children from Viena, and the ultimate children's transport Kindertranport, on May 14, 1940, from Holland with 74 children.

1945–1960[edit]

The Jewish-Dutch population after the Second World War is marked by certain significant changes: emigration; a low birth rate; and a high intermarriage rate. After the Second World War and the devastations which were caused by the Holocaust, thousands of surviving Jews made aliyah to Mandate Palestine, later Israel. Aliyah from the Netherlands initially surpassed that of any other Western nation. Israel is still home to some 6,000 Dutch Jews. Others emigrated to the United States. There was a high assimilation and intermarriage rate among those who stayed. As a result, the Jewish birth rate and organized community membership dropped. In the aftermath of the Holocaust, relations with non-Jews were friendly, and the Jewish community received reparations payments.[10]

In 1947, two years after the end of the Second World War in the Netherlands, the total number of Jews as counted in the population census was just 14,346 (down from a count of 154,887 by the German occupation force in 1941). Later, this number was adjusted by Jewish organisations to some 24,000 Jews living in the Netherlands in 1954 – nevertheless an enormous decrease compared to the number of Jews counted in 1941 – a number which was also disputed as the German occupation force counted Jews on basis of race, which meant that for example hundreds of Christians of Jewish heritage were also included in the Nazi census (according to Raul Hilberg in his book 'Perpetrators Victims Bystanders: the Jewish Catastrophe, 1933–1945', "the Netherlands ... [had] 1,572 Protestants [of Jewish heritage in 1943] ... There were also some 700 Catholic Jews living in the Netherlands [during the Nazi occupation] ...")

In 1954, the geographical spread of Dutch Jews in the Netherlands was as follows (province; number of Jews):

- Groningen – 242

- Friesland – 155

- Drenthe – 180

- Overijssel – 945

- Gelderland – 997

- Utrecht – 848

- North Holland – 15,446 (including 14,068 in Amsterdam)

- South Holland – 3,934

- Zeeland – 59

- North Brabant – 620

- Limburg – 297

- Total – 23,723

1960s and 1970s[edit]

The 1960s and 1970s saw a lowering birth rate among Dutch Jews, while intermarriage increased; the intermarriage rate of Jewish males was 41% and of Jewish women 28% in the period of 1945–1949. Figures from the 1990s saw an increase in intermarriage to some 52% of all Jewish marriages. Among so-called "father Jews",[11][12] the intermarriage rate is as high as 80%.[13] Some within the Jewish community try to counter this trend, creating possibilities for single Jews to come in contact with other single Jews, like the dating site Jingles[14] and Jentl en Jewell.[15] According to a research by the Joods Maatschappelijk Werk (Jewish Social Service), a large number of Dutch Jews received an academic education, and there are proportionally more Jewish Dutch women in the labor force than non-Jewish Dutch women.

1980s and onwards[edit]

The Jewish population in the Netherlands became more internationalized, with an influx of mostly Israeli and Russian Jews during the last decades. Approximately one in three Dutch Jews has a non-Dutch background. The number of Israeli Jews living in the Netherlands (concentrated in Amsterdam) runs in the thousands (estimates run from 5,000 to 7,000 Israeli expatriates in the Netherlands, although some claims go as high as 12,000),[16] although only a relatively small number of these Israeli Jews is connected to one of the religious Jewish institutions in the Netherlands. Some 10,000 Dutch Jews have emigrated to Israel in the last couple of decades.

At present, there are approximately 41,000 to 45,000 people in the Netherlands who are either Jewish as defined byhalakha (Rabbinic law), defined as having a Jewish mother (70% – approximately 30,000 persons) or who have a Jewish father (30% – some 10,000 – 15,000 persons; their number was estimated at 12,470 in April 2006).[17][18] Most Dutch Jews live in the major cities in the west of the Netherlands (Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, Utrecht); some 44% of all Dutch Jews live in Amsterdam, which is considered the centre of Jewish life in the Netherlands. In 2000, 20% of the Jewish-Dutch population was 65 years or older; birth rates among Jews were low. An exception is the growing Orthodox Jewish population, especially in Amsterdam.

There are currently some 150 synagogues present in the Netherlands, of which some 50 are still used for religious services.[19] Large Jewish communities in the Netherlands are found in Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague; smaller ones are found throughout the country, in Alkmaar, Almere, Amersfoort, Amstelveen, Bussum, Delft, Haarlem, Hilversum,Leiden, Schiedam, Utrecht and Zaandam in the western part of the country, in Breda, Eindhoven, Maastricht, Middelburg,Oosterhout and Tilburg in the southern part of the country, and in Aalten, Apeldoorn, Arnhem, Assen, Deventer,Doetinchem, Enschede, Groningen, Heerenveen, Hengelo, Leeuwarden, Nijmegen, Winterswijk, Zutphen and Zwolle in the eastern and northern parts of the country.

Religion[edit]

Some 9,000 Dutch Jews, out of a total of 30,000 (some 30%), are connected to one of the seven major Jewish religious organizations. Smaller, independent synagogues exist as well.[citation needed]

Orthodox Judaism[edit]

Most affiliated Jews in the Netherlands (Jews part of a Jewish community) are affiliated to the Nederlands Israëlitisch Kerkgenootschap (Dutch Israelite Church) (NIK), which can be classified as part of (Ashkenazi) Orthodox Judaism. The NIK has approximately 5,000 members, spread over 36 congregations (of whom 13 in Amsterdam and surroundings alone) in 4 jurisdictions (Amsterdam, The Hague, Rotterdam and the Interprovincial Rabbinate), making it considerably larger than the Union of Liberal Synagogues (LJG) and thirteen times as large as the Portuguese Israelite Religious Community (PIK). In Amsterdam alone, the NIK governs thirteen functioning synagogues. The NIK was founded in 1814, and at its height in 1877, it represented 176 Jewish communities. This went down to 139 communities prior to World War II, and 36 communities today. Besides governing some 36 congregations, the NIK also holds responsibility for more than 200 Jewish cemeteries throughout the Netherlands (on a total number of Jewish cemeteries of 250).

In 1965 Rabbi Meir Just was appointed Chief Rabbi of the Netherlands, a position he held until his death in April 2010.[20]

The small Portugees-Israëlitisch Kerkgenootschap (Portuguese Israelite Religious Community) (PIK), which is Sefardic, has a membership of some 270 families, and is concentrated in Amsterdam. It was founded in 1870. Throughout history, Sefardic Jews in the Netherlands, in contrast to their Ashkenazi co-religionists, have concentrated in only a few communities: Amsterdam, The Hague, Rotterdam, Naarden and Middelburg. Only the one in Amsterdam has survived the Holocaust and is still active.

There are three Jewish schools in Amsterdam, all situated in the Buitenveldert neighbourhood (Rosh Pina, Maimonides and Cheider). One of these (Cheider) is affiliated with Haredi Orthodox Judaism. Chabad has eleven rabbis, in Almere, Amersfoort, Amstelveen, Amsterdam, Haarlem, Maastricht, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht. The head shluchim in the Netherlands are rabbis I. Vorst and Binyomin Jacobs. The latter is chief rabbi of the Interprovinciaal Opperrabbinaat (the Dutch Rabbinical Organisation)[21] and vice-president of Cheider. Chabad serves approximately 2,500 Jews in Holland, and an unknown number in the rest of the Netherlands.

Reform Judaism[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Progressive Judaism |

|---|

| Regions |

|

| Beliefs and practices |

Though the number of Dutch Jews is decreasing,[citation needed] the last decades have seen a growth of Liberal Jewish communities throughout the country. Introduced by German-Jewish refugees in the early 1930s, nowadays some 3,500 Jews in the Netherlands are linked to one of several Liberal Jewish synagogues throughout the country. Liberal synagogues are present in Amsterdam (founded in 1931; 725 families – some 1,700 members), Rotterdam (1968), The Hague (1959; 324 families), Tilburg (1981), Utrecht (1993), Arnhem (1965; 70 families), Haaksbergen (1972), Almere (2003), Heerenveen (2000; some 30 members) and Zuid-Laren. TheVerbond voor Liberaal-Religieuze Joden in Nederland (LJG) (Union for Liberal-Religious Jews in the Netherlands) (to which all the communities mentioned above are part of) is affiliated to the World Union for Progressive Judaism. On 29 October 2006, the LJG changed its name to Nederlands Verbond voor Progressief Jodendom (NVPJ) (Dutch Union for Progressive Judaism). The NVPJ has ten rabbis; some of them are: Menno ten Brink, David Lilienthal, Awraham Soetendorp, Edward van Voolen, Marianne van Praag, Navah-Tehillah Livingstone, Albert Ringer, Tamara Benima.

A new Liberal synagogue has been built (2010) in Amsterdam, 300 meters away from the current synagogue. This was needed since the former building became too small for the growing community. The Liberal synagogue in Amsterdam receives approximately 30 calls a month by people whom wish to convert to Judaism. The number of people actually converting is much lower. The number of converts to Liberal Judaism may be as high as 200 to 400, on an existing community of approximately 3,500.

Amsterdam is also home to Beit Ha'Chidush, a progressive religious community which was founded in 1995 by Jews with secular as well as religious backgrounds who felt it was time for a more open, diverse and renewed Judaism. The community accepts members from all kinds of backgrounds, including homosexuals and half-Jews (including Jews with a Jewish father, the first Jewish community in the Netherlands to do so). Beit Ha'Chidush has links to Jewish Renewal in the United States, and Liberal Judaism in the United Kingdom. Rabbi for the community was German-born Elisa Klapheck, the first female rabbi of the Netherlands, and is now Clary Rooda. The community uses the Uilenburger Synagoge (nl) in the center of Amsterdam. A new progressive unaffiliated group named Beth Shoshanna (nl)[22] has started in the old synagogue of Deventer in 2009.

Klal Israël is an independent Jewish congregation founded in the end of 2005, since 2009 affiliated with the Jewish Reconstructionist Federation. It holds its roots in Progressive Judaism. The congregation holds services in the historic synagogue of Delft, once every two weeks.

Conservative Judaism[edit]

Masorti Judaism was introduced in the Netherlands in 2000, with the founding of a Masorti community in the city of Almere. In 2005 Masorti Nederland (Masorti Netherlands) had some 75 families, primarily based in the greater Amsterdam-Almere region. The congregation uses the 19th century synagogue in the city of Weesp. Its first rabbi is David Soetendorp (1945).

Education and Youth[edit]

Jewish schools[edit]

There are three Jewish schools in the Netherlands, all in Amsterdam and affiliated with the Nederlands Israëlitisch Kerkgenootschap (NIK). Rosj Pina is a school for Jewish children ages 4 through 12. Education is mixed (boys and girls together) despite its affiliation to the Orthodox NIK. It is the largest Jewish school in the Netherlands. As of 2007, it had 285 pupils enrolled.[23] Maimonides is the largest Jewish high school in the Netherlands. It had some 160 pupils enrolled in 2005. Although founded as a Jewish school and affiliated to the NIK, it has a secular curriculum.[24] Cheider, started by former resistance fighter Arthur Juda Cohen, presents education to Jewish children of all ages, and of the three schools, is the only one with a Haredi background. Girls and boys are educated in separate classes. The school has some 200 pupils.[25]

Jewish youth[edit]

There are several Jewish organisations in the Netherlands focused on Jewish youth. They include:

- Bne Akiwa Holland (Bnei Akiva),[26] a religious Zionist youth organisation.

- CIJO,[27] the youth organisation of CIDI (Centrum Informatie en Documentatie Israël), a political Jewish youth organisation.

- Gan Israel Holland,[28] the Dutch branch of the youth organisation of Chabad.

- Haboniem-Dror, a socialist Zionist youth movement.

- Ijar,[29] a Jewish student organisation

- Moos,[30] an independent Jewish youth organisation

- Netzer Holland,[31] a Zionist youth organisation aligned to the NVPJ

- NextStep,[32] the youth organisation of Een Ander Joods Geluid

Jewish health care[edit]

There are two Jewish nursing homes in the Netherlands. One, Beth Shalom, is situated in Amsterdam at two locations, Amsterdam Buitenveldert and Amsterdam Osdorp. There are some 350 elderly Jews currently residing in Beth Shalom.[33]Another Jewish nursing home, the Mr. L.E. Visserhuis, is located in The Hague.[34] It is home to some 50 elderly Jews. Both nursing homes are aligned to Orthodox Judaism; kosher food is available. Both nursing homes have their own synagogue.

There is a Jewish wing at the Amstelland Hospital in Amstelveen. It is unique in Western Europe in that Jewish patients are cared with according to Orthodox Jewish law; kosher food is the only type of food available at the hospital.[35] The Jewish wing was founded after the fusion of the Nicolaas Tulp Hospital and the (Jewish) Central Israelite Patient Care in 1978.

The Sinai Centrum (Sinai Center) is a Jewish psychiatric hospital located in Amsterdam, Amersfoort (primary location) andAmstelveen, which focuses on mental healthcare, as well as caring for and guiding persons who are mentally disabled.[36]It is the only Jewish psychiatric hospital currently operating in Europe. Originally focusing on the Jewish segment of the Dutch population, and especially on Holocaust survivors who were faced with mental problems after the Second World War, nowadays the Sinai Centrum also provides care for non-Jewish victims of war and genocide.

Jewish media[edit]

Jewish television and radio in the Netherlands is produced by NIKMedia. Part of NIKMedia is the Joodse Omroep,[37] which broadcasts documentaries, stories and interviews on a variety of Jewish topics every Sunday and Monday on theNederland 2 television channel (except from the end of May until the beginning of September). NIKMedia is also responsible for broadcasting music and interviews on Radio 5.

The Nieuw Israëlitisch Weekblad is the oldest still functioning (Jewish) weekly in the Netherlands, with some 6,000 subscribers. It is an important news source for many Dutch Jews, focusing on Jewish topics on a national as well as on an international level. The Joods Journaal (Jewish Weekly)[38] was founded in 1997 and is seen as a more "glossy" magazine in comparison to the NIW. It gives a lot of attention to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Another Jewish magazine published in the Netherlands is the Hakehillot Magazine,[39] issued by the NIK, the Jewish Community of Amsterdam and the PIK. Serving a more liberal Jewish audience, the NVPJ publishes its own magazine, Levend Joods Geloof (Living Jewish Faith), six times a year;[40] serving this same audience, Beit Ha'Chidush publishes its own magazine as well, called Chidushim.[41]

There are a couple of Jewish websites focusing on bringing Jewish news to the Dutch Jewish community. By far the most prominent is Joods.nl, which gives attention to the large Jewish communities in the Netherlands as well as to theMediene, to Israel as well as to Jewish culture and youth.

Amsterdam[edit]

Amsterdam's Jewish community today numbers about 15,000 people.[citation needed] A large amount lives in the neighbourhoods of Buitenveldert, the Oud-Zuid and the River Neighbourhood. Buitenveldert is considered a popular neighbourhood to live in; this is due to its low crime-rate and because it is considered to be a quiet neighbourhood.

Especially in the neighbourhood of Buitenveldert there's a sizeable Jewish community. In this area, Kosher food is widely available. There are several Kosher restaurants, two bakeries, Jewish-Israeli shops, a pizzeria and some supermarkets host a Kosher department. This neighourbood also has a Jewish elderly home, an Orthodox synagogue and three Jewish schools.

Cultural distinctions[edit]

Uniquely in the Netherlands, Ashkenazi and Sephardi communities coexisted in close proximity. Having different cultural traditions, the communities remained generally separate but their geographical closeness resulted in cross-cultural influences not found elsewhere. Notably, in the early days when small groups of Jews were attempting to establish communities, they were bound to use the services of rabbis and other officials from either culture, depending on who was available.

The close proximity of the two cultures inevitably led to intermarriage at a higher rate than was known elsewhere, and in consequence many Jews of Dutch descent have family names that seem to belie their religious affiliation. Particularly unusual, all Dutch Jews have for centuries named children after the children’s grandparents, which is otherwise considered exclusively a Sephardi tradition. (Ashkenazim elsewhere traditionally avoid naming a child after a living relative.)

In 1812, while the Netherlands was under Napoleonic rule, all Dutch residents (including Jews) were obliged to register surnames with the civic authorities, a practice which among Jews had previously been followed only by Sephardim. As a result of the compulsory registration and other extant records, it became clear that while the Ashkenazim had been avoiding civic registration, many had nevertheless been using an unofficial system of surnames for hundreds of years.

Also under Napoleonic rule, in 1809 a law was passed obliging Dutch Jewish schools to teach in Dutch and Hebrew. This effected the exclusion of other languages and in due course, Yiddish, the lingua franca of Ashkenazim, and Portuguese, the previous language of the Sephardim, practically ceased to be spoken among Dutch Jews. Certain Yiddish words have been adopted into the Dutch language, especially in Amsterdam (which is also called Mokum, from the Hebrew word for town or place, makom), where the historically large Jewish community has had a significant influence on the local dialect. There are several other Hebrew words that can be found in the local dialect including: Mazzel from mazel, which is the Hebrew word for luck or fortune; Tof which is Tov in Hebrew meaning good (as in מזל טוב – Mazel tov), and Goochem in Hebrew Chacham or Hakham, meaning wise, sly, witty or intelligent, where the Dutch g is pronounced similarly to the 8th letter of the Hebrew Alphabet the guttural Chet or Heth.

Economic influences[edit]

Jews played a major role in the development of Dutch colonial territories and international trade, and many Jews in former colonies have Dutch ancestry. However, all the major colonial powers were competing fiercely for control of trade routes; the Dutch were relatively unsuccessful and during the 18th century, their economy went into decline. Many of the Ashkenazim in the rural areas were no longer able to subsist and they migrated to the cities in search of work. This caused a large number of small Jewish communities to collapse completely (ten adult males were required for major religious ceremonies). Entire communities then migrated to the cities where the Jewish populations swelled explosively. In 1700, the Jewish population of Amsterdam was 6,200, with Ashkenazim and Sephardim in almost equal numbers. By 1795 the figure was 20,335, the vast majority being poor Ashkenazim.

Because Jews were obliged to live in specified Jewish quarters, there was severe overcrowding. By the mid-nineteenth century, many were migrating to other countries where the advancement of emancipation offered better opportunities (seeChuts).

See also[edit]

- Beit Ha'Chidush

- Jewish Amsterdam

- Jewish Eindhoven

- Jewish Maastricht

- Jewish Tilburg

- Klal Israël

- List of Dutch Jews

- List of Jews deported from Wageningen (1942-1943)

List of Dutch Jews

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This page is a list of notable Dutch Jews, arranged by field of activity.

Contents

[hide]Economists[edit]

Historians[edit]

- Evelien Gans (Jewish father)[3]

Jurists[edit]

- Tobias Asser (1838-1913), Nobel Prize for Peace winner in 1911[4]

- Eduard Meijers (1880-1954), founding father of the Dutch new civil code[5]

- Max Moszkowicz

Mathematicians[edit]

Actors and comedians[edit]

Actors[edit]

- Edwin de Vries (born 1950), actor and director (Jewish father)[7]

Comedians[edit]

- Raoul Heertje (born 1963), stand-up comedian [8]

- Micha Wertheim (born 1972), stand-up comedian

Artists[edit]

Painters[edit]

- Helen Berman (born 1936)[9]

- Paul Citroen (1896–1983)[10]

- Jozef Israëls (1824–1911)[11]

- Isaac Israëls (1865–1934)[12]

- Marianne Franken (1884–1945)[13]

- Eduard Frankfort (1864–1920)[14]

- Jesse Kluytmans (1841–????)[13]

- Martin Monnickendam (1874–1943)[15]

- Max Bueno de Mesquita (1913–2001)[16]

- Benjamin Prins (1860–1934)[17]

- Mommie Schwarz (1876-1942)[18]

Other artists[edit]

- Joseph Jessurun de Mesquita (1865–1890), photographer[19]

- Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita (1868–1944), graphic artist[20]

- Joseph Mendes da Costa (1863–1939), sculptor[21]

Politicians[edit]

- Lodewijk Asscher - PvdA politician, born in Amsterdam (Jewish father) [22]

- Onno Hoes, mayor of Maastricht, chairman CIDI[23]

- Uri Rosenthal, former Minister of Foreign Affairs, political scientist[24]

- Harry Wijnschenk, former MP [25]

Businesspeople and entrepreneurs[edit]

- Samuel van den Bergh (1864–1941), co-founder of Unilever, politician[26]

- Israël Kiek (1811–1899), photographer[27]

- Abraham Icek Tuschinski (1886–1942), cinema entrepreneur and Holocaust victim[28]

Sports people[edit]

Field hockey[edit]

- Carina Benninga, Olympic champion, bronze

Gymnastics[edit]

- Estella Agsteribbe, Olympic champion (team combined exercises), killed by the Nazis in Auschwitz

- Elka de Levie, Olympic champion (team combined exercises)

- Helena Nordheim, Olympic champion (team combined exercises), killed by the Nazis in Sobibór

- Anna Polak, Olympic champion (team combined exercises), killed by the Nazis in Sobibór

- Judijke Simons, Olympic champion (team combined exercises), killed by the Nazis in Sobibór

Soccer (association football)[edit]

- Daniël de Ridder (born 1984) Celta de Vigo forward winger/attacking midfielder (Wigan Athletic & U21 national team; Jewish-Israeli mother)[29][30][31]

- Sjaak Swart, Ajax and Dutch international footballer (Jewish father)[32]

Tennis[edit]

- Tom Okker, won 1973 French Open Men's Doubles (w/John Newcombe), 1976 US Open Men's Doubles (w/Marty Riessen), highest world ranking # 3 in singles, and # 1 in doubles

Volleyball[edit]

- Aryeh "Arie" Selinger, US & Dutch, player & coach [33]

- Avital Selinger, Olympic silver

Writers[edit]

- Manja Croiset, author and poet

- Gideon Levy (Dutch journalist) (born 1970)

- Anne Frank

- Xaviera Hollander, author (Jewish father)[32]

- Leon de Winter, author

Princess Margriet of the Netherlands

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Princess Margriet Francisca of the Netherlands (born 19 January 1943) is the third daughter of Queen Juliana and Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands. As an aunt of the reigning monarch, King Willem-Alexander, she is a member of the Dutch Royal House and currently eighth and last in the line of succession to the Dutch throne.[1]

Princess Margriet has often represented the monarch at official or semi-official events. Some of these functions have taken her back to Canada, her country of birth, and to events organised by the Dutch merchant navy of which she is a patron.

Contents

[hide]Birth in Canada[edit]

The Princess was born in The Ottawa Hospital,[2] Ottawa, Ontario, as the family had been living in Canada since June 1940 after the occupation of the Netherlands by Nazi Germany. The maternity ward of Ottawa Civic Hospital in which Princess Margriet was born was temporarily declared to be extraterritorial by the Canadian government.[3][4] Making the maternity ward outside of the Canadian domain caused it to be unaffiliated with any jurisdiction and technically international territory. This was done to ensure that the newborn would derive her citizenship from her mother only, thus making her solely Dutch.

It is a common misconception that the Canadian government declared the maternity ward to be Dutch territory. Since Dutch nationality law is based primarily on the principle of jus sanguinis it was not necessary to make the ward Dutch territory for the Princess to become a Dutch citizen. Since Canada followed the rule of jus soli, it was necessary for Canada to disclaim the territory temporarily so that the Princess would not, by virtue of birth on Canadian soil, become a Canadian citizen.

Namesake and christening[edit]

She was named after the marguerite, the flower worn during the war as a symbol of the resistance to Nazi Germany. (See also the book When Canada Was Home, the Story of Dutch Princess Margriet, by Albert VanderMey, Vanderheide.)

Princess Margriet was christened at St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church, Ottawa, on 29 June 1943. Her godparents included the President of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Queen of the United Kingdom, theCrown Princess of Norway, Martine Roell (who was a lady-in-waiting to Princess Juliana in Canada) and The Dutch Merchant Fleet.[5]

After the war[edit]

It was not until August 1945, when the Netherlands had been liberated, that Princess Margriet first set foot on Dutch soil. Princess Juliana and Prince Bernhard returned to Soestdijk Palace in Baarn, where the family had lived before the war.

It was while she was studying at Leiden University that Princess Margriet met her future husband, Pieter van Vollenhoven. Their engagement was announced on 10 March 1965, and they were married on 10 January 1967 in The Hague, in the St. James Church.[6] It was decreed that any children from the marriage would be styled HH Prince/Princess of Orange-Nassau, van Vollenhoven, titles that would not be held by their descendants.

The Princess and her husband took up residence in the right wing of Het Loo Palace in Apeldoorn. In 1975 the family moved to their present home, Het Loo, which they had built on the Palace grounds.

Children[edit]

Princess Margriet and Pieter van Vollenhoven have four sons:

- Prince Maurits (born 17 April 1968) m. Marilène van den Broek (born 4 February 1970) on 29 May 1998. They have three children:

- Anastasia (Anna) Margriet Joséphine van Lippe-Biesterfeld van Vollenhoven (born 15 April 2001)

- Lucas Maurits Pieter Henri van Lippe-Biesterfeld van Vollenhoven (born 26 October 2002)

- Felicia Juliana Benedicte Barbara van Lippe-Biesterfeld van Vollenhoven (born 31 May 2005)

- Prince Bernhard (born 25 December 1969) m. Annette Sekrève (born 18 April 1972) on 6 July 2000. They have three children:

- Isabella Lily Juliana van Vollenhoven (born 14 May 2002)

- Samuel Bernhard Louis van Vollenhoven (born 25 May 2004)

- Benjamin Pieter Floris van Vollenhoven (born 12 March 2008)

- Prince Pieter-Christiaan (born 22 March 1972) m. Anita van Eijk (born 27 October 1969) on 25 August 2005. They have two children:

- Emma Francisca Catharina van Vollenhoven (born 28 November 2006)

- Pieter Anton Maurits Erik van Vollenhoven (born 19 November 2008)

- Prince Floris (born 10 April 1975) m. Aimée Söhngen (born 19 October 1977) on 20 October 2005. They have three children:

- Magali Margriet Eleonoor van Vollenhoven (born 9 October 2007)

- Eliane Sophia Carolina van Vollenhoven (born 5 July 2009)

- Willem Jan Johannes Pieter Floris van Vollenhoven (born July 1 2013)

Royal role and patronages[edit]

Princess Margriet is an active member of the Royal Family, representing the Monarch at a range of events. [7]

She is particularly interested in health care and cultural causes. From 1987 to 2011 she was vice-president of the Netherlands Red Cross, who set up the Princess Margriet Fund in her honour. She is a member of the board of theInternational Federation of National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

From 1984 to 2007 Princess Margriet was President of the European Cultural Foundation, who set up the Princess Margriet Award for Cultural Diversity in acknowledgement of her work.

She is a member of the Honorary Board of the International Paralympic Committee. [8]

Titles and styles[edit]

- 19 January 1943 – 10 January 1967: Her Royal Highness Princess Margriet of the Netherlands, Princess of Orange-Nassau, Princess of Lippe-Biesterfeld[9]